Buying goods and services safely

How to keep fraud out of your business Like most businesses – large and small – you probably need to buy in goods and services. Regardless of whether you rely on a handful of local traders or a long international supply chain, you could be at risk of fraud. Catching fraud early is vital. You will prevent losses, protect your reputation and you might even save the business from collapse. This guide explains how fraud can occur during the buying process and looks at the practical things you can do to stay safe.

Buying goods and services safely

Like most businesses – large and small – you probably need to buy in goods and services.

Regardless of whether you rely on a handful of local traders or a long international supply chain, you could be at risk of fraud.

Catching fraud early is vital. You will prevent losses, protect your reputation and you might even save the business from collapse.

What is procurement fraud?

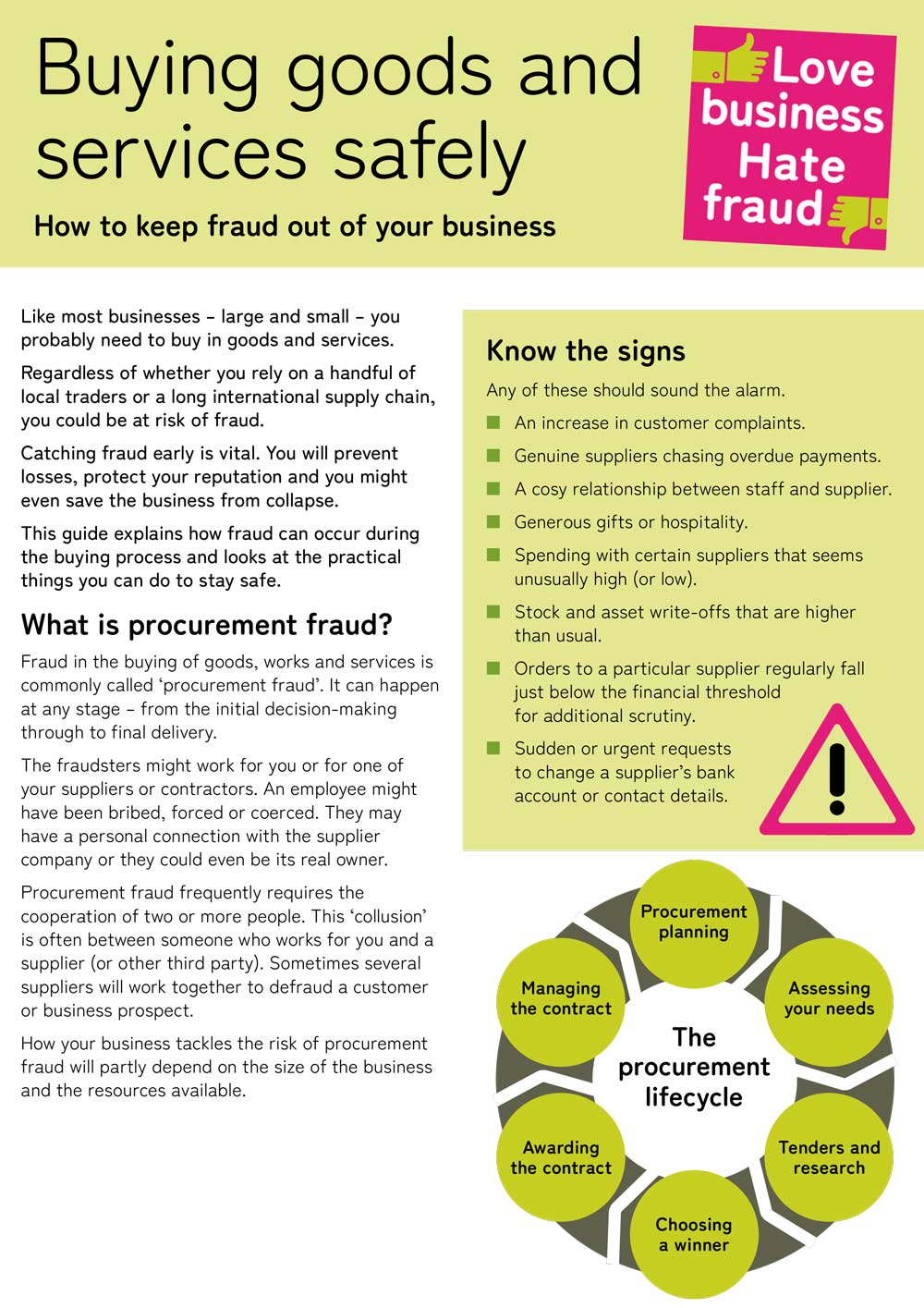

Fraud in the buying of goods, works and services is commonly called ‘procurement fraud’. It can happen at any stage – from the initial decision-making through to final delivery.

The fraudsters might work for you or for one of your suppliers or contractors. An employee might have been bribed, forced or coerced. They may have a personal connection with the supplier company or they could even be its real owner.

Procurement fraud frequently requires the cooperation of two or more people. This ‘collusion’ is often between someone who works for you and a supplier (or other third party). Sometimes several suppliers will work together to defraud a customer or business prospect.

How your business tackles the risk of procurement fraud will partly depend on the size of the business and the resources available.

Case study

A set-building subcontractor, who submitted fake invoices worth £33,000 to a TV studio, was jailed for 18 months after pleading guilty. His fraud went on for eight months even though he’d been employed for just a week. The fraud was spotted only when the work available declined sharply but the fake invoices kept arriving.

Know the signs

Any of these should sound the alarm.

- An increase in customer complaints.

- Genuine suppliers chasing overdue payments.

- A cosy relationship between staff and supplier.

- Generous gifts or hospitality.

- Spending with certain suppliers that seems unusually high (or low).

- Stock and asset write-offs that are higher than usual.

- Orders to a particular supplier regularly fall just below the financial threshold for additional scrutiny.

- Sudden or urgent requests to change a supplier’s bank account or contact details.

Beware of risks throughout the life cycle

If your contract management procedures are not up to scratch, fraud can easily go undetected.

Planning and assessing

One of your employees may try to ensure that a certain supplier wins a particular contract. You can end up paying for things you don’t need, or which are overpriced or otherwise unsuitable.

Tendering and researching

A group of suppliers can prevent competition by colluding. They might take turns to bid for contracts, agree to divide up the market, deliberately bid too high or not at all, or agree to fix prices. One of your employees could be involved, perhaps by selling or leaking information.

Choosing and awarding

After bids have been received, one of your employees might try to influence the evaluation and selection process to make sure a certain supplier wins.

Managing the contract

Suppliers might deliberately overcharge. Delays and overruns can be faked to justify extra charges. An employee might intentionally over-order for their own use or resale. Or they can collude with the supplier to pay for goods or services that are never delivered.

Common examples to look out for

Fictitious suppliers

Corrupt employees and third parties might have created fake companies solely for the purpose of siphoning off your procurement budget.

Collusion between suppliers

- Bid rotation: Several suppliers take turns to ‘win’ your business. The winning bidder may go on to subcontract to the others. Prices are sometimes higher as a result.

- Market sharing: Suppliers collude to divide up the market geographically or in some other way. Again, there may be subcontracting to ‘losing’ bidders and prices will tend to be higher.

- Cover pricing: A ‘winner’ is designated beforehand and guaranteed to win because everyone else inflates their bids. The ‘losers’ may receive side payments.

- Bid suppression: A group of suppliers voluntarily agree to withhold their bids, or coercion is used to prevent others from bidding. The ‘winner’ controls prices and sometimes pays off the rest by subcontracting.

- Price fixing: Bidders keep prices high by agreeing to submit coordinated bids, many of which are designed to fail.

Kickbacks or bribes

An employee receives cash or gifts (such as sports tickets or an expensive holiday) in return for making sure that the supplier wins the work.

Employees collude with suppliers

This might involve sharing technical or financial information, or tailoring the contract or specification to suit.

Inflated invoices

Overcharging for real deliveries or charging for extras never delivered.

Product substitution

Poor-quality, second-hand or counterfeit goods or services are delivered but charged for at full price.

Misappropriation of assets

Staff steal items bought for the business, including deliberately over-ordering for their own personal use or resale.

Case study

Two ‘rival’ suppliers of furniture parts to well-known brands were fined £2.8m for colluding to carve-up the market and inflate the prices their customers paid. The fraud was uncovered by a tip-off. Investigators found evidence of meetings at which executives shared normally confidential pricing information and promised not to approach each other’s customers.

Protecting your business

Some simple steps can make your business safer.

Do due diligence

Make sure that suppliers, consultants and contractors really do exist. Check their VAT registrations (where appropriate), references from previous clients, and bank and registered office details. Review publicly available information online, including Companies House. And it is always a good idea to cross-check supplier details (addresses, bank accounts and so on) against those you hold for employees.

Split staff duties

Segregate responsibilities for ordering/commissioning and the making of payments wherever possible. Ideally no one person should be solely responsible for procurement decisions.

Record conflicts of interest, gifts and hospitality

Create formal policies and procedures that apply to everyone. Keep a record of all conflicts of interest, gifts and hospitality (given and received), especially where they concern suppliers, subcontractors and intermediaries. Review and update these regularly.

Monitor spending and contract management

Review spending – both with suppliers and by employees (on credit cards and using petty cash). Investigate anomalies as soon as possible. Monitor deliveries of goods or services against the original specifications. Match payments to purchase orders.

Make sure you have a clear process for making amendments to contracts and orders after work has begun.

Check inventory and assets

To be sure you are receiving exactly what you have paid for, always check delivery notes and the products delivered. Keep inventory and asset registers up to date and monitor their usage regularly. To prevent deliveries going astray think about providing suppliers with a list of approved delivery addresses.

Maintain a contracts database

Ask staff to record all decisions and actions relating to the award, implementation and management of each individual contract.

Case study

A manager at a drinks company took bribes of cash and football tickets worth £1.5m over almost a decade. In exchange, his favoured suppliers won real and bogus contracts at inflated prices, and received confidential commercial information. Bribes were paid via a network of shell companies. The scheme came to light when one of the bribers accidentally included a rival’s confidential price information in an expense claim.

A checklist

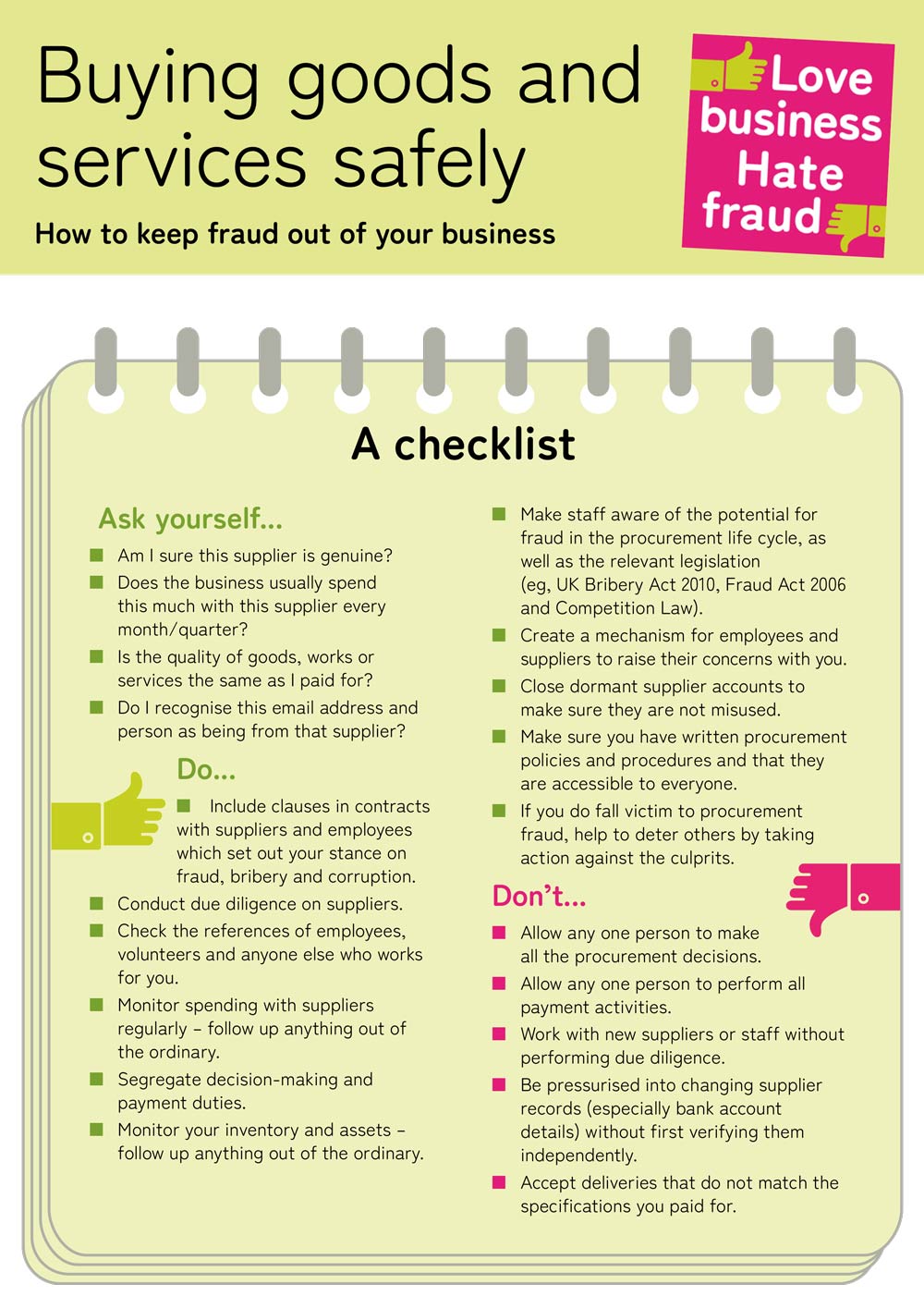

Ask yourself …

- Am I sure this supplier is genuine?

- Does the business usually spend this much with this supplier every month/quarter?

- Is the quality of goods, works or services the same as I paid for?

- Do I recognise this email address and person as being from that supplier?

Do …

- Include clauses in contracts with suppliers and employees which set out your stance on fraud, bribery and corruption.

- Conduct due diligence on suppliers.

- Check the references of employees, volunteers and anyone else who works for you.

- Monitor spending with suppliers regularly – follow up anything out of the ordinary.

- Segregate decision-making and payment duties.

- Monitor your inventory and assets – follow up anything out of the ordinary.

- Make staff aware of the potential for fraud in the procurement life cycle, as well as the relevant legislation (eg, UK Bribery Act 2010, Fraud Act 2006 and Competition Law).

- Create a mechanism for employees and suppliers to raise their concerns with you.

- Close dormant supplier accounts to make sure they are not misused.

- Make sure you have written procurement policies and procedures and that they are accessible to everyone.

- If you do fall victim to procurement fraud, help to deter others by taking action against the culprits.

Don’t …

- Allow any one person to make all the procurement decisions.

- Allow any one person to perform all payment activities.

- Work with new suppliers or staff without performing due diligence.

- Be pressurised into changing supplier records (especially bank account details) without first verifying them independently.

- Accept deliveries that do not match the specifications you paid for.

This practical guide highlights the many risks of procurement fraud. But business fraud comes in many other guises. It makes good business sense to find out more. Go to lovebusiness-hatefraud.org.uk or follow the campaign on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Thanks to Laura Hough from BDO LLP for kindly writing this guide.

Published June 2022. © Fraud Advisory Panel and Barclays 2022.

Fraud Advisory Panel and Barclays will not be liable for any reliance you place on the information in this material. You should seek independent advice.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Licence.